Self-assessment

Under Australia’s self-assessment system taxes including, notably, income tax and the goods and services tax, are based on returns by each taxpayer where responsibility is on the taxpayer to ensure statements and representations made to the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) reflected in those returns are true and correct.

Penalties when returns are not true and correct

When a taxpayer departs from true and correct disclosure to the ATO, penalties, including base penalties, for false and misleading statements to the ATO, unarguable tax positions and tax schemes are imposed by Division 284 of Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act (C’th) 1953.

To understand the base penalty regime in Division 284 it is helpful to consider simplified categories of a taxpayer’s disclosures relevant to their return viz:

- those items that are straight forward where the taxpayer understands how the item should be returned and its impact on the taxpayer’s tax liability, and

- those items which are more complex or difficult where the taxpayer does not fully understand how the item should be returned and its impact on the taxpayer’s tax liability.

It is expected, or at least hoped, that matters in the first category will greatly outnumber matters in the second category. Still an item in the second category may involve a large liability and there may be a need for the taxpayer to resolve the complexity or difficulty, by taking tax advice or perhaps by obtaining a binding private ruling from the Commissioner of Taxation about that item to ensure the item is correctly returned.

As a general proposition it can be said that, unless other mitigating factors apply, failure to correctly return an item in the first category attracts the 75% “intentional disregard” base penalty and that failure to correctly return an item in the second category attracts the 50% “recklessness” base penalty based on the reasoning below:

Deceptively understating assessable income or overstating allowable deductions etc.

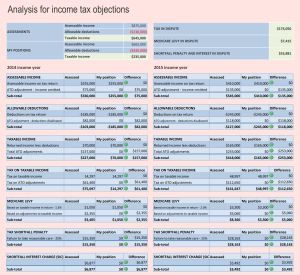

If a taxpayer omits an item in the first category from an income tax return which understates true and correct taxable income then the highest base penalty of 75% for intentional disregard of a taxation law under the table in section 284-90 can be imposed. This isn’t the only liability that follows from a tax review, audit or investigation of a tax return. In addition to section 284-90 base penalties, the taxpayer will be held separately liable for the tax on the taxable income that should have been returned, medicare levy, and, to reflect the time value of taxes outstanding to the ATO, the shortfall interest charge and the general interest charge, etc when an amended assessment is raised to amend the original assessment which was not true and correct.

Base penalties, including the 75% intentional disregard base penalty, are imposed on a case by case basis. Thus the ATO will infer from the way the return was completed and surrounding facts whether there was intentional disregard of taxation law justifying imposition of a 75% intentional disregard base penalty. Similar considerations as arise as to whether there was fraud or evasion (which impacts on when an amended assessment can be raised) including whether the conduct giving rise to the omission of assessable income or the overstatement of allowable deductions or offsets etc. was deceptive or calculated, or whether the conduct could be explained as some sort of mistake, which attracts a lesser penalty, are relevant.

50% “recklessness” base penalty applied in PSI cases

The recent personal services income (PSI) cases of Douglass v. Commissioner of Taxation [2018] AATA 3729 (3 October 2018) and Fortunatow v. Commissioner of Taxation [2018] AATA 4621 (14 December 2018) illustrate how the 50% “recklessness” base penalty under the table in section 284-90, one rung down from the highest 75% intentional disregard base penalty, can be applied to a taxpayer who fails to correctly apply taxation law to matters in the second category.

Both cases involved the application of the personal services income measures in Part 2-42 of Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA) 1997 to the income of professionals (an engineer and a business analyst respectively) which was alienated from the respective individual professionals by arrangements using related companies reducing their overall income tax liabilities.

Complex or difficult?

The personal services income measures in Part 2-42 are relatively complex involving multi-tiered considerations of various tests even though the Commissioner of Taxation expressed this view in the objection decision in Douglass (from para 110 of the AAT decision):

The attribution rule of the PSI is not an overly complex area of the relevant law. There was readily available information on the operation of the PSI rules set out on the ATO website. It was also explained in the Partnership tax return instruction and in the Personal Services income schedule instruction that accompanied the tax return guide for company, partnerships and trusts. You did not make further enquiries to check the correct tax treatment of your PSI.

In both cases, the taxpayers primarily relied on the “results test” in section 87-18 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 to establish that, in each case, a personal service business was being carried on so that alienated income for the personal services of the individuals would not be attributed to the individuals under Part 2-42. On the facts of each case, each AAT found that the individual was not engaged to produce a result in accord with section 87-18 and so could not satisfy the “results test”.

Recklessness

Also, in both cases, the AAT was critical of the way in which each taxpayer tried to ascertain their respective liabilities under the personal services income measures. In Douglass the taxpayer did not take a cogent advice on how the PSI measures can apply. In Fortunatow the taxpayer had received an advice on asset protection considerations from a tax lawyer which inferred that PSI advice should be taken. But that PSI tax advice was not taken by the taxpayer in Fortunatow.

In each case the AAT referred to BRK (Bris) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation (2001) ATC 4111 where Cooper J. at p.4129 considered “recklessness”:

Recklessness in this context means to include in a tax statement material upon which the Act or regulations are to operate, knowing that there is a real, as opposed to a fanciful risk, that the material may be incorrect, or be grossly indifferent as to whether or not the material is true and correct, and that a reasonable person in the position of the statement-maker would see there was a real risk that the Act and regulations may not operate correctly to lead to the assessment of the proper tax payable because of the content of the tax statement. So understood, the proscribed conduct is more than mere negligence and must amount to gross carelessness.

It was unhelpful to the case of the taxpayer in Fortunatow that the taxpayer had been made aware by his tax advice that the PSI measures had potential application to him and that there was a real risk that he was not correctly complying with tax laws. The tax advice he received went no further than saying that income would not be attributed under the PSI measures if there was a personal services business but the taxpayer could not show that he had been advised that he had been carrying on a personal services business.

Obligation on the taxpayer to be correct

These AAT decisions leave little doubt that the responsibility on a taxpayer to correctly address and resolve complex or difficult tax questions in completing their tax returns is serious and far reaching. Ordinarily this means that a taxpayer will need a cogent tax advice or will need to take other steps to demonstrate that the taxpayer has adequately addressed each question to mitigate the “real risk” that the taxpayer’s position on a complex question in a tax return is incorrect to avoid “recklessness”.

Interaction with other base penalties and where taking cogent tax advice is desirable

This removes the opportunity to shirk a complex question or issue in a tax return and to rely on the difficulty or character of the question or issue to assert that some lesser base penalty, such as the 25% base penalties under Division 284 either for failure:

- to take reasonable care; or

- to take a reasonably arguable position;

is applicable.

Base penalties under Division 284 of Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act (C’th) 1953 apply on the basis that the highest base penalty applies to the exclusion of the other applicable base penalties.

Complex PSI cases demonstrate how self-assessment works

The above personal service income cases provide good case studies of how base penalties under Division 284 are likely to apply in cases where a category 2 complex issue arises and a taxpayer fails to adequately address the issue in their return to the ATO.

Although the ATO cannot apply a 75% intentional disregard base penalty where the taxpayer was without intent to disregard taxation law which was or may have been too complex for the taxpayer to appreciate; the 50% recklessness base penalty, on the next rung down, can nevertheless be applied because of the taxpayer’s failure to deal with that complexity. Complexity is dealt with by taking cogent tax advice from a professional tax adviser for example. It can be seen that the 50% recklessness base penalty is thus integral to taxpayers taking responsibility for true and correct disclosure to the ATO under the self-assessment system.