Those seeking the small business capital gains tax (CGT) concessions in the 2018 and later income years need to be wary of modified small business CGT concession integrity rules which apply from 8 February 2018 by virtue of Schedule 2 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Tax Integrity and Other Measures) Act 2018 (TIOMA).

The small business CGT concessions in Division 152 of the Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA) 1997 may look straight forward but there are subtle complications within the misnamed “basic” conditions for the relief which can be matrixlike. The small business CGT concessions are generous so perhaps it is right that rules to protect their integrity, as ramped up by the TIOMA, are more complicated than the rules that ordinarily impose a CGT liability on sales of small business related CGT assets.

Share or interest sales need to meet additional basic conditions

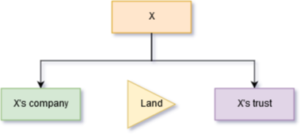

For CGT events involving sales of shares in companies or interests in trusts “additional” basic conditions have commenced with the TIOMA. The additional basic conditions go further than what I describe here. In this post I wish to focus on the significance of the dual $6m maximum net asset value tests that the TIOMA initiates. So in the below considerations I am going to assume that the other basic conditions for the small business CGT concessions, including the additional basic conditions, such as the dual active asset test, which also needs to be considered following the introduction of the TIOMA, will be met.

The dual MNAV and SBE tests

The dual $6m maximum net asset value (MNAV) tests are alternative tests with the similarly dual small business entity ($2m aggregated turnover) (SBE) tests which apply where the small business CGT relief is sought on a sale of shares in a company or an interest in a trust. The dual MNAV tests and SBE tests separately test both the taxpayer (“you”) and the object entity which is the relevant company or trust in which the shares are or interest is held by the taxpayer as the case may be. To obtain relief under the basic conditions, and under the additional basic conditions set out in sub-section 152-10 as revised by the TIOMA, the dual tests must be separately satisfied to obtain any small business CGT concession relief:

| Taxpayer must satisfy | AND | Object entity must satisfy |

| MNAV test or SBE test | Modified MNAV test or SBE test and carried on business up to day of sale |

When the object entity MNAV test becomes vital

In practice, there is a significant slew of sales of shares or trust interests where the object entity won’t satisfy the SBE test because of:

- an aggregated annual turnover of the object entity of more than $2 million; or

- alternatively, the object entity may satisfy that SBE test but paragraph 152-10(2)(a) may apply because the object entity ceased to carry on its business some time before the sale.

In those cases the object entity also needs to satisfy the MNAV test even where the taxpayer has separately satisfied either of the MNAV test or the SBE test or both.

Satisfaction of the MNAV test by the object entity may thus be vital to the availability of the small business CGT concessions to a taxpayer selling shares or a trust interest. Where the object entity, let us say a private company with multiple owners, is worth more than $6m overall, this may well be a problem for minority owners who otherwise are:

- on or over the 20% significant individual/CGT stakeholder threshold; or

- with net asset value (NAV) under $6m who sell their shares looking for the small business CGT concessions.

The Explanatory Memorandum with the TIOMA gives the following example:

Example 2.4: Investment in large business

Karen carries on a small consulting business as a sole trader. She is a CGT small business entity (according to the general rules) for the 2019-20 income year. Karen also owns 30 per cent of the shares in Big Pty Ltd, a large private company with annual turnover in excess of $20 million in both the 2018-19 and 2019 CGT assets exceeds $100 million throughout this period. On 1 October 2019, Karen sells her shares in Big Pty Ltd. She would not be eligible to access the Division 152 CGT concessions for any resulting capital gain. Even if Karen satisfies the other basic conditions for relief, she cannot satisfy the new condition. Big Pty Ltd is not a CGT small business entity in the 2019-20 income year. It also does not satisfy the maximum net asset value test in relation to the capital gain, as its net assets exceed $6 million immediately prior to the CGT event happening (being in excess of $100 million for the entire income year).

MNAV test complexities

Like the SBE test with aggregated turnover of the taxpayer, affiliates and their connected entities, compliance with the MNAV test relies on, or more specifically NAV (net asset value) must stay under the relevant $6m limit after, aggregation.

Before aggregation is considered there is a flip side: the exclusions from the MNAV test: The substantial exclusions are confined to individual taxpayers viz. interests in an individual’s main residence, personal use assets, superannuation and insurance: section 152-20 of the ITAA 1997. The other exclusions in this section are largely to prevent accounting anomalies with:

- accounting provisions; and

- the double counting of the value of an asset indirectly held in an entity and the value of the stake in the entity including the asset, representing the same value, in NAV.

Liabilities are also excluded from NAV where they relate to assets so the MNAV test can be a maximum net asset value test.

The value of assets that are not excluded are tallied in NAV when applying the MNAV test. Then aggregation must be done. Just like with the complexity of small business CGT concessions integrity more generally, MNAV tests and sometimes qualification for the concessions, involve a hierarchy of constructs which, for the purposes of illustration, can be loosely compared to the pieces on a chessboard one’s opponent in chess may hold:

Chess piece: King

Div 152 construct: The taxpayer

Comment: If the King falls, it’s game over. If either NAV of the taxpayer or (modified) NAV of the object entity exceeds $6m in each required MNAV test the basic condition is failed unless there is a pathway to compliance through the SBE test as described above.

Chess piece: Queen

Div 152 construct: An affiliate

Comment: Although an affiliate is not the taxpayer (or object entity), the NAV of the affiliate also counts/aggregates to the taxpayer (or object entity) when applying the MNAV test to the taxpayer (or object entity), in all directions including NAV aggregated from connected (and Oconnected in the case of an object entity – see below) entities of the affiliate.

Chess piece: Bishop

Div 152 construct: Connected entities

Comment: The whole of the NAV of the connected entity (excluding the exclusions described above) counts in the MNAV test. So if a taxpayer, or an affiliate, has a stake of 50% in a connected entity X, all (100%) of X’s net value is aggregated to the taxpayer’s NAV (including NAV relating to the stake in X of minority stakeholders unrelated to the taxpayer or affiliate). If Y is a connected entity of X then aggregate all (100%) of Y’s net value to the taxpayer’s NAV too.

Chess piece: Knight

Div 152 construct: Oconnected entities

Comment: The Oconnected entity (my terminology – I thought of using “controlled entity” which is in contrast to a connected entity which can either control or be controlled by the other entity it is connected to. But controlled entity is misleading for, as we shall see, only a 20% stake, hardly control in any sense, is needed to trigger this link) is a new construct introduced with the additional basic conditions in the TIOMA relating to the object entity.

The NAV of a Oconnected entity is aggregated to the NAV of the object entity but it is look through forward to aggregate and not look through back too (unlike “controlled by the other entity” which can connect too to a connected entity). An example is needed to explain constructs here: So if O, an object entity controls Q an Oconnected entity, due to a 20% or greater stake in Q, and P is another unrelated stakeholder in Q; the value of Q owned by P is included in the NAV of Q aggregated to O (see the outcome of that in the below Example 2.5 drawn from the Explanatory Memorandum) but the NAV of P and its connected entities is excluded from the NAV of O (if they are not separately affiliated/connected to O).

In chess the Knight moves in a weird way so the Knight is the allegory chosen here!

Chess piece: Pawn

Div 152 construct: Asset or investment of the above

Comment: A pawn generally moves one space in chess. $1 in value of an asset or investment owned by a taxpayer or object entity, which is not excluded, counts $1 to the NAV of the taxpayer or an object entity. $1 in value of an asset or investment owned by affiliates, connected entities and Oconnected entities, which are not excluded, count $1 to the affiliate, connected entity and Oconnected entity, as the case may be, but if that NAV is in an affiliate, a connected entity or a Oconnected entity of the taxpayer or object entity in applying the dual tests, the whole NAV of the relevant entity is aggregated to the taxpayer/object entity, not its proportionate NAV based on percentage stake. i.e. A percentage stake is only used for an interest in an entity where the entity the interest is held in is not an affiliate, connected entity or, in the case of the object entity MNAV test, an Oconnected entity.

I don’t play chess and I accept my chess analogy with the workings of the MNAV tests is far from perfect. My endeavour is to make this consideration of the hierarchical workings of the MNAV tests a little more comprehendible and so, perhaps, if you are still reading by this point I have succeeded? If the comparison with chess conveys:

- that counts of over $6m by either of the taxpayer NAV or the object entity NAV will generally mean failure of a basic condition for the Division 152 CGT relief so can lead to loss of the game; and

- that high value pieces accelerate aggregation of NAV to the $6m limit. That is they can move more than one space: every $1 of a stake a taxpayer (or object entity) in a connected entity (or Oconnected entity), and affiliates and their connected entities without needing any stake in the affiliate of the taxpayer (or object entity) will generally aggregate more than $1 to NAV as the value of others’ stakes in these entities will count to the NAV attributed to the taxpayer (or object entity) too.

The modified MNAV test of the object entity & the modified Oconnected entity

The NAV for controlled entities of an object entity is different due to sub-paras 152-10(2)(c)(iii), (iv) & (v) in the TIOMA:

The threshold between unrelated entity, counted simply as an asset or investment (pawn) to NAV and connected entity (bishop) consistent with other tests of control in the ITAA 1936 and the ITAA 1997 is 40% with a discretion given to the Commissioner where:

- there is 40% or over and under a 50% stake; and

- it can be established to the Commissioner that some other entity controls the entity that would otherwise be the connected entity.

In practice this means expect the Commissioner to de-connect A from connection with X if A owned 48% of X and B (unconnected to A) owned 52% of X.

When applying the object entity MNAV test, sub-paras 152-10(2)(c)(iii), (iv) & (v) have operation so that the threshold is lowered to a 20% stake in the other entity. That is enough “control” to make the other entity, otherwise an asset or investment, an Oconnected entity (knight). This is apparent from another example in the Explanatory Memorandum with the TIOMA:

Example 2.5: Indirect investment in large business

Tien owns 20 per cent of the shares in Investment Co, a company that carries on an investment business. Investment Co is a CGT small business entity (according to the general rules) for the 2020-21 income year. Investment Co holds 20 per cent of Van Co, a transport company. Van’s assets mean that it is not a CGT small business entity in the 2020-21 income year and does not satisfy the maximum net asset value test at any point during the income year. On 15 May 2021, Tien sells his shares in Investment Co. He is not eligible to access the Division 152 CGT concessions for any resulting capital gain. Even if Tien satisfies the other conditions, he cannot satisfy the new condition requiring the object entity be a CGT small business entity or satisfy the maximum net asset value test due to the modifications that apply when determining this matter for the purposes of this condition. For the purposes of this condition, Investment Co is considered to be connected with Van Co, as Investment Co holds 20 per cent of Van.

As stated in the table above there is no look through back so in a case where an object entity has a stake of 21% of X, the NAV in entities connected to X by virtue of the remaining 79% stakes in X are excluded from the object entity NAV although the NAV of the assets of X, including that relating to the other stakeholders, counts to the object entity NAV.