In EE&C Pty Ltd as Trustee for the Tarcisio Cremasco Family Trust v. Commissioner of Taxation (Taxation) [2018] AATA 4093 (30 October 2018) the taxpayer, after concluding a minute of terms of agreement with the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) on 18 January 2011, entered into a deed to settle a tax dispute with the Commissioner for the 1999 to 2005 years of income on 23 March 2011 (the Deed of Settlement).

In EE&C Pty Ltd as Trustee for the Tarcisio Cremasco Family Trust v. Commissioner of Taxation (Taxation) [2018] AATA 4093 (30 October 2018) the taxpayer, after concluding a minute of terms of agreement with the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) on 18 January 2011, entered into a deed to settle a tax dispute with the Commissioner for the 1999 to 2005 years of income on 23 March 2011 (the Deed of Settlement).

Assessments in line with settlement

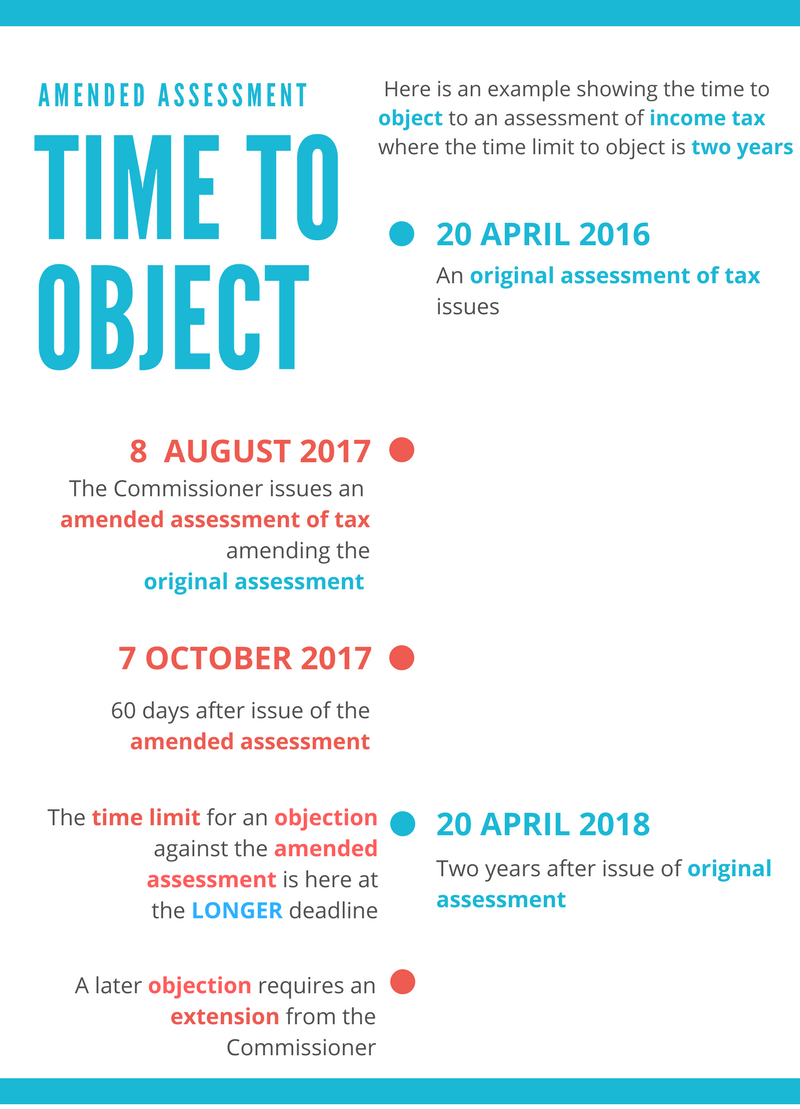

On 2 June 2011 the Commissioner issued a series of assessments for those years primarily increasing, and in some income years reducing, the taxable income of the taxpayer in line with the Deed of Settlement.

Under the contractual terms of the Deed of Settlement the taxpayer was precluded from objecting against the assessments which issued as negotiated and set out in the terms.

Despite that the taxpayer had its lawyers prepare and lodge “objections” against the 2 June 2011 assessments on 4 June 2014.

Right conferred by statute overrides the terms to settle?

Apparently the lawyer had explained to the taxpayer that the taxpayer’s right to object against a taxation assessment, or more precisely a “taxation decision” under Part IVC of the Taxation Administration Act (C’th) 1953 (the TAA), is a statutory right which had lead the taxpayer to understand that their right to object persisted despite the apparent waiver of their right to object against the assessments in the Deed of Settlement.

Commissioner relied on the taxpayer’s waiver in the Deed of Settlement

The Commissioner took a contrary view and refused to treat the 4 June 2014 “objections” as valid objections.

Waiver did impact the statutory right to object

The AAT found that the Commissioner was correct in his approach. Deputy President Forgie of the AAT concluded that, as the 4 June 2014 “objections” were invalid, the AAT had no jurisdiction to review how the Commissioner dealt with them under the TAA and the Administration Appeals Tribunal Act (C’th) 1975.

Capability to waive right to object/appeal an imperative in settling tax disputes

At paragraph 89 of the AAT decision, Deputy President Forgie described a functional imperative that a taxpayer can waive their statutory right to object or appeal to settle Part IVC review and appeal proceedings:

The authorities of Cox, Grofam, Fowles and Precision Pools all support the Commissioner’s reaching a settlement with the taxpayer. The taxpayer must be permitted to forego his rights of objection and review or appeal just as the Commissioner may fulfil his obligation to decide the objection and respond to the review or appeal in terms that do so but are reached by way of agreement with the taxpayer rather than by, for example, imposition of a decision of the Tribunal or judgment of the Court. Agreement may be reached before a taxpayer engages in the formal processes of taxation objection leading to an objection decision and on to review or appeal or at some point during the process.

Why a Part IVC right to object or appeal is a type of right that can be waived

The AAT drew a distinction between a statutory right that can be waived under a contract and a statutory right that cannot. At paragraph 90, Deputy President Forgie referred to the general rule, expressed by Higgins J. in Davies v. Davies [1919] HCA 17; (1919) 26 CLR 348, at p 362:

Anyone is at liberty to renounce a right conferred by law for his own sole benefit; but he cannot renounce a right conferred for the benefit of society.

and gave examples of other statutory rights where the recipient of the right may abandon the right or not pursue the right. It follows that as a taxpayer is the sole recipient of the legal right to object under Part IVC, the taxpayer is able to renounce that right in the course of settlement of a Part IVC dispute.