Laws reflect perspective. When the imposition of laws, especially taxes, turns on whether the taxpayer is a local (resident) or foreign (non-resident) then laws will be designed with elusion in mind so someone cannot elude being treated as:

- local if the burden and focus of the law (such as a tax) falls on locals; and

- foreign if the burden and focus of the law falls on foreigners.

Income tax – focus on locals

The Income Tax Assessment Act (C’th) (ITAA) 1936 overall might be considered to be in the former case in Australia. Although Australian non-resident income tax rates can be higher than resident rates, generally a wider range of activity of residents is taxable in Australia, and residents are subject to income tax on their worldwide income. Income tax collection under the ITAA 1936 and 1997 is mainly focussed on collecting income tax from residents. Certainly Australian locals can be income taxed with fewer international constraints.

Thus who is a “resident” or “resident of Australia” in the definition of these terms in sub-section 6(1) of the ITAA 1936 includes, among others: an Australian citizen whose domicile, by virtue of that citizenship, is in Australia unless the Commissioner of Taxation is satisfied the person’s permanent place of abode is outside of Australia. This definition part imposes a satisfaction hurdle without which an Australian citizen, with a domicile in Australia, will be an income tax resident with broad exposure to income tax under the ITAA 1936 and 1997.

Foreign acquisitions and takeovers – focus on foreigners

In contrast the burdens imposed by the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act (C’th) 1975 (FATA) in Australia are on foreigners and is so, along with the state and territory foreign person surcharges mentioned below, an example of the latter case in Australia. The FATA is concerned with the acquisition, monitoring and control of Australian real estate and other Australian-based investment interests by foreigners. The FATA obliges notification to the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB) of proposed acquisitions of specified types which can be approved or rejected by the Australian Treasurer on the recommendation of the FIRB.

Vacancy fee

A vacancy tax on foreigners commenced under the FATA as a measure to improve housing affordability for Australian locals in 2017. The vacancy fee is contained in Part 6A of the FATA under which a foreign person who owns a residential dwelling in Australia is charged an annual vacancy fee where the dwelling is not residentially occupied or rented out for more than 183 days in yearly periods which measure from the date of acquisition of ownership by the foreigner. The vacancy fee under Part 6A is imposed as a tax by section 5 of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Fees Imposition Act (C’th) 2015.

Vacancy fee rates

Vacancy fee rates are tethered to the FIRB fees (also imposed as taxes under the same section 5) applicable to a foreign person making an application to acquire the residential land. which is ad valorem based on the value of the real estate on acquisition. Here is an extract from a table with the ad valorem fees:

| Acquiring an interest in residential land where the price of the acquisition is… | Fee payable |

| less than $75,000 | $2,000 |

| between $75,000 – $1,000,000 | $6,350 |

| between $1,000,001 – $2,000,000 | $12,700 |

| between $2,000,001 – $3,000,000 | $25,400 |

Under section 4 of the FATA:

“foreign person” means:

section 4 of the FATA

(a) an individual not ordinarily resident in Australia; or

(b) a corporation in which an individual not ordinarily resident in Australia, a foreign corporation or a foreign government holds a substantial interest; or

(c) a corporation in which 2 or more persons, each of whom is an individual not ordinarily resident in Australia, a foreign corporation or a foreign government, hold an aggregate substantial interest; or

(d) the trustee of a trust in which an individual not ordinarily resident in Australia, a foreign corporation or a foreign government holds a substantial interest; or

(e) the trustee of a trust in which 2 or more persons, each of whom is an individual not ordinarily resident in Australia, a foreign corporation or a foreign government, hold an aggregate substantial interest; or

(f) a foreign government; or

(g) any other person, or any other person that meets the conditions, prescribed by the regulations.

It follows that any person, including an Australian citizen, can be a foreign person caught by these provisions however, under a convoluted exemption arrangement, Australian citizens who are not ordinarily resident in Australia are relieved from the vacancy fee.

Relief for non-resident Australian citizens

I understand that the relief works in this way:

Section 28 of the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Regulation 2015 [Select Legislative Instrument No. 217, 2015] (FATR 2015) prescribes every section of the FATA, aside from the definition of foreign person in section 4 itself and other provisions to which that definition relates to, as excluded provisions. (Bold emphasis added by me.)

Section 28 also carries a note which provides:

The effect of this Division is that acquisitions of interests of a kind mentioned in this Division are not significant actions, notifiable actions or notifiable national security actions, but are taken into account for the purposes of the definition of foreign person in section 4 of the Act.

Note to section 28 of the FTAR 2015

and

paragraph 35(1)(a) of FATR 2015 provides:

Acquisitions of any land by persons with a close connection to Australia

(1) The excluded provisions do not apply in relation to an acquisition of an interest in Australian land by any of the following persons:

(a) an Australian citizen not ordinarily resident in Australia;

…

paragraph 35(1)(a) of FATR 2015

There does not appear to be any further “close connection”, as referred to in the heading to section 35, required to trigger the exemption beyond being an Australian citizen in the case of paragraph 35(1)(a). That is: a non-resident Australian citizen has, by virtue of being a citizen, a close connection to Australia.

Application of the non-resident Australian citizen exemption to the vacancy fee?

The vacancy fee, though, is a tax imposed on a foreign person when a dwelling, already acquired by the foreign person, is not residentially occupied or rented out for more than 183 days in yearly period as stated above. Could it be that a foreign person, including a non-resident Australian citizen, will still be caught by the vacancy fee because the vacancy fee is concerned with omission to occupy or rent out property for more than 183 days over a yearly period and not with acquisition of the property so paragraph 35(1)(a) relief can’t be attracted?

The answer appears to be in section 115B of the FATA which scopes when vacancy fee liability under Part 6A arises. Section 115B provides:

Scope of this Division–persons and land

sub-section 115B(1) of the FATA

(1) This Division applies in relation to a person if:

(a) the person is a foreign person; and

(b) the person acquires an interest in residential land on which one or more dwellings are, or are to be, situated; and

(c) either:

(i) the acquisition is a notifiable action; or

(ii) the acquisition would be a notifiable action were it not for section 49 (actions that are not notifiable actions–exemption certificates).

Note: Regulations made for the purposes of section 37 may provide for circumstances in which this Division does not apply in relation to a person or a dwelling….

It follows that the provisions of “this Division”, which is Division 2 of Part 6A of the FATA and which contains the provision imposing vacancy fee liability, are excluded provisions and so vacancy fee liability on an omission to occupy or rent residential land, where the interest in that residential land was acquired by a non-resident Australian citizen under paragraph 35(1)(a) of FATR 2015, is not attracted by a non-resident Australian citizen purchaser of the residential land. That is so even though a non-resident Australian citizen is a foreign person caught by paragraph 115B(1)(a).

This is a very complicated way to exempt non-resident Australian citizens from treatment as foreigners. Couldn’t section 4 of the FATA just carve out non-resident Australian citizens from being foreign persons to broadly the same effect?

Adding to the confusion is FIRB Guidance Note 31 Who is a foreign person (1 July 2017) which refers to paragraph 15 of the decision in Wright v. Pearce (2007) 157 CLR 485 as guidance on the position with Australian citizens. This reference is actually in error and should be Wight v. Pearce (2007) 157 FLR 485 (not a decision of the High Court of Australia). In any case I can’t see where that reference has anything to say about resident and non-resident Australian citizens having a close connection to Australia, which, unlike being ordinarily resident in Australia which is the matter under consideration at paragraph 15 of the case, is the apparent touchstone of liability when paragraph 35(1)(a) of FATR 2015 is taken into account.

Comparison of the federal vacancy fee with state foreign person surcharge land tax and surcharge purchaser duty

The vacancy fee can apply over and above the foreign person surcharge land tax and surcharge purchaser duty imposed by Australian states introduced at around the same time also to achieve housing affordability for Australian locals.

The foreign person surcharges in New South Wales also adopt the “foreign person” formulation in section 4 of the FATA to pinpoint foreigners liable to the surcharges but with modifications including under paragraph 104J(2)(a) of the Duties Act (NSW) 1997:

(a) an Australian citizen is taken to be ordinarily resident in Australia, whether or not the person is ordinarily resident in Australia under that definition,

paragraph 104J(2)(a) of the Duties Act (NSW) 1997

which carves out non-resident Australian citizens from “foreign persons” and thus the complexity of excluded provisions from the FATR 2015, a Commonwealth statutory instrument, do not need to be contended with to find exemption for non-resident Australian citizens from the surcharges.

In making a comparison between the the federal vacancy fee on the one hand with state foreign person surcharge land tax on the other hand it should also be observed that the state foreign person land tax surcharges are generally imposed on foreigners per se, that is: whether the residential land is vacant for a period is immaterial. So omission by a foreign person to occupy or rent out property for more than 183 days generally means liability for both the federal vacancy fee and a state land tax surcharge will be attracted.

Temporary residents

When an individual owner of residential real estate is not an Australian citizen then whether the individual is ordinarily resident in Australia does become a touchstone for tax and surcharge liability as a “foreign person”. Sub-section 5(1) of the FATA provides:

(1) An individual who is not an Australian citizen is ordinarily resident in Australia at a particular time if and only if:

(a) the individual has actually been in Australia during 200 or more days in the period of 12 months immediately preceding that time; and

(b) at that time:

(i) the individual is in Australia and the individual’s continued presence in Australia is not subject to any limitation as to time imposed by law; or

(ii) the individual is not in Australia but, immediately before the individual’s most recent departure from Australia, the individual’s continued presence in Australia was not subject to any limitation as to time imposed by law.

Sub-section 5(1) of the FATA

A temporary resident for tax is someone who is not an Australian citizen or permanent resident who can stay in Australia under an immigration visa which, as a matter of course, will be a visa with a limitation as to the time the holder can stay in Australia.

A temporary resident is taxable for income tax only:

- on income derived in Australia; and

- on foreign income but only foreign income earned from employment or services performed overseas while a temporary resident.

A temporary resident is not income taxable on capital gains made on assets which are not Taxable Australian Property e.g. real estate.

See the ATO website here: https://is.gd/DbJJmk

A temporary resident is a foreign person under the FATA no matter how long the individual is present in Australia until and unless the temporary resident becomes a permanent resident or an Australian citizen due to paragraph 5(1)(b) of the FATA as set out above.

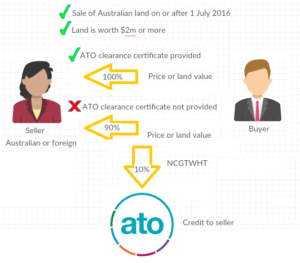

Temporary residents can acquire residential real estate, including established residential premises with conditions, under the FATA and FIRB regime however the vacancy fee and the state and territory foreign person surcharges can apply to their interests in Australian residential land.

Permanent residents

As permanent resident visa holders are not subject to any limitation as to time they can be in Australia imposed by law the requirements in paragraph 5(1)(a) of the FATA are of ongoing concern to them until and unless they become Australian citizens. That is: a permanent resident who has not actually been in Australian for 200 days in the applicable preceding twelve months is taken not to be ordinarily resident in Australia despite their visa.

If such a permanent resident owns Australian real estate but has not been in Australia for the required 200 days in an applicable twelve months then he or she is a foreign person for that year. Then the vacancy fee and the state and territory foreign person surcharges can apply to a permanent resident’s interests in Australian residential land.