In my August 2022 blog:

The capital gains tax main residence exemption, affordable housing and caps – The capital gains tax main residence exemption, affordable housing and caps https://wp.me/p6T4vg-rg

I considered the generous, unlimited and regressive CGT main residence (MR) exemption under Australian income tax and pondered the extent to which the CGT MR exemption has contributed to housing unaffordability. As I said in that post, for those who occupy and turnover homes they own in Australia, the CGT MR exemption delivers uncapped tax free uplifts in wealth as prices rise.

But the line can be overstepped.

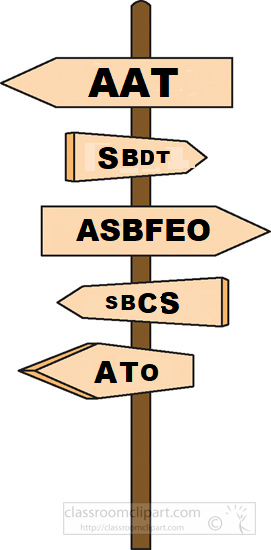

A’s residential building project

Let us take A who has significantly benefitted from tax free CGT uplifts on previous sales of A’s former homes:

- A acquires real estate which can be subdivided and on which two homes can be built.

- A’s idea with this acquisition is to move in to one of the homes (Lot 1) once it is built and occupiable.

- But A doesn’t plan to live in Lot 1 long term. A’s plans are to sell Lot 1 and Lot 2 with completed dwellings for a hoped for profit.

- Will the CGT MR exemption enable A to enjoy profits from the project tax free?

The Commissioner of Taxation can treat the above development for sale as an adventure in the nature of trade to sell the land and buildings for profit. The occupation by A of Lot 1 as A’s home is incidental to the project. This differs from another case where, say, B uses real estate, on which B’s existing home is located, for a development where B subdivides, builds and sells where there was clearly an initial time pre-project where the real estate was only used by B as B’s home.

Proceeds or profits from sales and ordinary income

Where a project is a development for sale at a profit, such as in A’s case for the whole time and, in B’s case, for the phase of development to sale, the proceeds or profits can be treated as ordinary income by the Commissioner based on cases and tax principles referred to in:

Taxation Ruling TR 92/3 Income tax: whether profits on isolated transactions are income

in which profits or gains in the ordinary course of business and from profit-making undertakings or schemes are considered.

Where proceeds or profits from sales are ordinary income arising either in the ordinary course of business or in a profit-making venture and also produce (otherwise taxable) capital gains then, due to section 118-20 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997, the proceeds or profits are treated as ordinary income and capital gains are not taxed. That is CGT does not apply and CGT principles, concessions and exemptions don’t apply to gains or losses made on income account.

So in A’s case, where the proceeds or profits from the sales of Units 1 and 2 are ordinary income:

- no CGT MR exemption can be applied to reduce tax on Unit 1 as there is no taxable capital gain; and

- further, no 50% CGT discount can be applied to reduce the extent to which proceeds or profits on sales are included in A’s assessable income as ordinary income

even though A is a resident individual generally entitled to such capital gain concessions.

Commissioner on the lookout

A’s plans to sell are not necessarily:

- going to be obvious to; or

- reported to;

the Commissioner particularly in the early stages of the A’s project. However that should change once Lot 1 and Lot 2 do sell. That is because:

- the Commissioner is on the lookout for residential real estate developments that are an adventure in the nature of trade and are an enterprise under goods and services tax (GST) rules:

Miscellaneous Taxation Ruling MT 2006/1 The New Tax System: the meaning of entity carrying on an enterprise for the purposes of entitlement to an Australian Business Number

- and it is Australian Business Number and GST information gathering by the Commissioner that may well reveal that A’s project is to develop and sell. The project can then be a review or audit target where proceeds and profits have not been returned by A as ordinary income.

New residential premises and GST taxable supplies

The sales of Units 1 and 2 are taxable supplies of new residential premises for GST where the sales happen within five years of when Units 1 and 2 are built and occupied as residences.

Generally the sale of a someone’s home is not treated as a taxable supply however that reassurance, considered at paragraph 11 of:

Goods and Services Tax Ruling GSTR 2003/3 Goods and services tax: when is a sale of real property a sale of new residential premises?

does not apply if the sale occurs as part of a profit making undertaking of scheme viz. where the supply is in the course of an enterprise and is not a mere realisation of the owner’s home: see paragraph 263 of MT 2006/1 et al.

Project trading stock or taxation of project profit?

What of B? How would B be taxed on income account when B’s earlier use of real estate was exclusively as B’s private home? When B sells B will be dealing with two events treated like sales for tax over an earlier and a later period. CGT and the CGT MR exemption can apply up to when B’s property is put to B’s development for sale project. But at that point B can be taken to have put the property to use as trading stock and section 70-30 of the ITAA 1997 applies to treat B as having sold the property and as having re-acquired the property as trading stock even though B continues to own the property [possibilitity 1].

In:

Taxation Determination TD 92/124 Income tax: property development: in what circumstances is land treated as ‘trading stock’?

the Commissioner states:

Land is treated as trading stock for income tax purposes if:

• it is held for the purpose of resale; and

• a business activity which involves dealing in land has commenced.

Even where the development for sale is not considered to be a “business activity”, but is nonetheless an isolated transaction within the ambit of TR 92/3; B’s profits, not B’s sale proceeds, can comprise the assessable income of B from the the development [possibility 2]. Those profits are based on the value of the property as a cost at the time the property is ventured to the development based on the High Court decision in F.C. of T. v. Whitfords Beach Pty. Ltd. (1982) HCA 8; 150 CLR 355.

The use as a home phase and the project development to sale phase are treated separately for tax either with possibility 1 and possibility 2.

GST, enterprise and creditable acquisitions

As A’s (or B’s) project leads to taxable supplies of new residential premises it will follow that A’s project is an enterprise requiring A to be registered for GST: see MT 2006/1. When that is understood by A, A may then register for the GST on a timely basis positioning A to more easily claim project expenses as creditable acquisitions and obtain GST credit or refunds.

That opportunity gets complicated where the new dwellings on Lots 1 and 2 may come to be used by A once built – say privately as A’s main residence, or say where held and used to earn rent, rather than sold, in which cases creditable acquisition claims on activity statements may need to be adjusted under GST rules due to A’s change in creditable purpose.

C the builder

Let us now consider C who, like A, has significantly benefitted from tax free uplifts, questionably, on previous sales of C’s former homes using the CGT MR exemption. But C is or has become a professional builder and C’s buy, build/renovate and sell for a profit can be understood and characterised as C’s business activity/profit making venturing after C’s real estate owning history is fully understood. The frequency and amount of those previous tax free uplifts taken with claims of the CGT MR exemption is a part of that history.

The cases and tax principles referred to TR 92/3 mean that C can still be taxed on income account, and cannot access the CGT MR exemption on this next project, even where C uses a dwelling built/renovated by C as C’s home during times when the dwellings C builds or renovates become occupiable.

Cases raising the income/capital dichotomy and these complications do not necessarily have the same tax outcomes and will turn on their own whole factual story.