As I mention in my 2015 blog post on the onus of proof:

The burden of proof in a tax objection

the onus on a taxpayer is an outlier and “reversed” when compared to the onus in other kinds of legal disputes.

Even when compared to the civil case onus, where disputes are also resolved on a balance of probabilities, the tax onus of proof is unusual. It is unlike the civil case standard which generally requires a litigant taking civil action to prove their case. That differs from disputes over Australian tax assessments where it is the taxpayer who must prove their position taken in their tax filings.

Beginnings of onus on the taxpayer

This has long been the case with Australian income tax even before the introduction of the self-assessment system in the late 1980s. Paragraph 190(b) of the Income Tax Assessment Act (ITAA) 1936, which imposed the burden of proof on taxpayers on objections and appeals over tax assessments, was in the original 1936 legislation.

Advent of self-assessment

In a sense tax legislation caught up with paragraph 190(b) with the onset of self-assessment in the late 1980s. The self-assessment system moved responsibility to assess one’s tax viz. to get tax filings right, wholly onto the taxpayer. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) website explains how self-assessment works:

we accept the information you give us is complete and accurate. We will review the information you provide if we have reason to think otherwise

Self-assessment and the taxpayer

Mutual reliance

It is a corollary of reliance on the taxpayer to get their tax filings right that a taxpayer can also demonstrate the completeness and accuracy of those filings when called on to do so by an ATO review, audit or investigation.

This proposition is made clearer when considered in the wider context of the body of Australian taxpayers meeting their tax obligations. Taxpayers, who can demonstrate accuracy and justify their tax filings, expect, or might be entitled to mutually expect, that other taxpayers, under the same obligations and contributing to the same pool of revenue; are also able to so demonstrate.

How the tax burden of proof can work

Let us say:

- a taxpayer T returns no income in an income year;

- the ATO reveals that T has received $1m in that period;

- T asserts that the $1m was a gift given to T by an overseas relative, and that is why T believes T’s income tax return was correct; and

- the ATO see a possibility that the $1m could have been income of T and T’s claim of a gift may not be true.

With the onus of proof on T, T must produce the information which supports T’s claim of a gift and T’s return of no income. That seems reasonable in the context of the $1m receipt being T’s own affair with which T is familiar enough to have excluded from T’s income in T’s income tax return. Having omitted to return $1m that way it follows that it should be up to T to demonstrate that the $1m is not T’s income on review.

If the onus of proof were the other way, and on the Commissioner, then where the Commissioner has scant information to demonstrate that the $1m or some part of it was income and the Commissioner may then be unable to positively prove the $1m was income of T so:

- T would avoid tax liability on the $1m even though the $1m may have been T’s income; and

- it would be in T’s interests to conceal information, including information about the possible income character of the $1m from the Commissioner, which is then unavailable to the Commissioner or costly to the ATO to establish with other means or from other sources, rather than to disclose information to positively show that the $1m was not T’s income which T would be compelled to do if the onus of proof is on T.

Parliamentary inquiry

A House of Representatives Standing Committee on Tax and Revenue (Committee) inquiry into tax administration has made recommendations on 26 October 2021 including for:

- increase in transparency of and communication by the ATO of ATO compliance activities;

- reversal of the onus of proof (from the taxpayer to the Commissioner) after a certain period where the Commissioner asserts there has been fraud or evasion;

- introduction of a 10 year time limit on the Commissioner for amendment of assessments where there has been fraud or evasion; and

- a moratorium on collection of tax debts by the Commissioner until a taxpayer has had the opportunity to dispute the debt.

The complexity issue

The long understood weakness with the self-assessment system, particularly with income tax collection in Australia, is the complexity of tax laws: see https://go.ly/x0MIU from the Australian Parliamentary website. This was not a significantly lesser weakness under the predecessor system where ATO resources in the ATO assessment process where sparse especially to assess activity where compliance with complex laws was in issue. Since self-assessment began income tax laws have only increased in complexity and, demonstrably, in volume. Yet, over the same period there has been:

- improvement in the drafting, clarity and usability of tax laws epitomised by the ITAA 1997 and its style;

- a release and expansion of public and private rulings, determinations and guidance on tax laws and guidance on the completion of tax returns; and

- access to them over the internet.

Role of professional tax advisers

Even before these advancements under self-assessment, 97% of corporate taxpayers and 74% of individual taxpayers used tax agents to assist them with meeting their tax obligations. Clearly tax agents and other professional tax advisers continue as a vital resource to taxpayers, especially business taxpayers, albeit at cost; to help them ensure obligations to comply with tax laws, especially complex laws, are met.

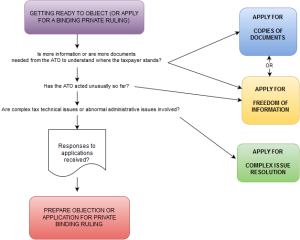

When the ATO overreaches

A difficulty I have faced in tax disputes is where a client does have information or proof which adequately does demonstrate the position taken in a tax filing but the ATO does not accept that information as sufficient proof. A related difficulty is where complex law is involved leading to protracted difference with the ATO over how tax law applies to what a taxpayer has done.

Taxpayers, especially business taxpayers reliant on professional tax advisers, are up for significant inconvenience, costs and expenses while a dispute with the Commissioner continues including where disputes arise when the taxpayer has made little or no mistake. The use of extensive debt collection powers by the Commissioner before disputes resolve is rightly a matter of controversy in tax disputes where:

- it can be established that the tax dispute is genuine; and

- deferral of the disputed tax debt poses no or minimal risk of permanent loss to the revenue and the community.

It could well be that there needs to be greater control and oversight of the Commissioner’s use of collection powers in these cases as there appears to be unconstrained and disproportionate use of them by the ATO when risks of loss to the revenue may have been low. The recommendation for checks and further transparency about ATO use of its compliance powers thus makes sense. Unfortunately debt collection in Australia, including collection from business, frequently involves unscrupulous and globally mobile debtors and even the Commissioner is not always well placed to judge risks of loss to the revenue or not of using the range of collection powers available to the Commissioner. It seems inevitable that some uses of collection powers by the Commissioner are not always going to appear proportionate when considered in retrospect.

Limitation periods

The limitation periods imposed under section 170 of the ITAA 1936 are already a departure from the taxpayer expectation, related to the expectation described above, that other taxpayers will pay tax based on the way they have filed or demonstrably should have filed their taxes. Amendments are restricted after expiry of limitation periods which also means the expectation can no longer be met by assessment amendment. The limitation periods, or periods of review, are there to ensure that the Commissioner and taxpayers properly finalise tax liabilities broadly not only within the expectation but also expeditiously without the prejudice to the other party of delay. Veracity of tax filings get harder to prove after a longer period of time especially once records are archived or lost beyond the expiry of record-keeping obligations to keep those records. Belated moves to amend can thus be unfair on the other party for that reason and for others.

Fraud and evasion

The reversal of the onus of proof proposed by the Committee seems limited and justifiable as a narrow exception. It would only apply where the Commissioner alleges fraud or evasion and only after a “certain” period has elapsed. In other words the onus of proof would remain on the taxpayer to disprove fraud or evasion if the Commissioner makes the allegation (which the Committee proposes must be signed off by a senior executive service (SES) officer of the ATO) within that period. But after that period it is only then proposed that the onus is to move to the Commissioner to prove fraud or evasion.

Alleging it for the right reasons

I have been involved in tax disputes where the Commissioner has alleged fraud or evasion even though available facts are just as much explainable by taxpayer inadvertance without there having been fraud of evasion. It was apparent in those disputes that the Commissioner was alleging fraud or evasion because the period for amendment of assessments, which can be as little as two years under section 170, in the absence of fraud or evasion, had expired. The difficulty for a taxpayer, with the onus of proof on the taxpayer, is that if the Commissioner makes a fraud or evasion allegation it is then up to the taxpayer to disprove it under current law: Binetter v FC of T; FC of T v BAI [2016] FCAFC 163 and, it follows, to disprove it at a time which may be remote from when the taxpayer may have had access to or opportunity to obtain evidence to disprove it.

It is perverse that, under current rules, the Commissioner can use unsubstantiated fraud and evasion claims against taxpayers to overcome a limitation period bar that would otherwise block the Commissioner from amending a tax assessment. That may well justify the Committee’s recommendations that the onus of proof of fraud or evasion in these delayed cases should move to the Commissioner but that the onus of proof remain on the taxpayer with respect to disproving other aspects of an assessment.

10 year limitation period for fraud and evasion cases?

But is it also necessary to impose a 10 year limitation period where there has been fraud or evasion by a taxpayer once:

- SES officer sign-off is required for making a fraud or evasion allegation; and

- the onus of proof of fraud or evasion is imposed on the Commissioner;

as also recommended?

Why would or should a taxpayer whose filing is tainted by demonstrable fraud or evasion, and is thus improper, be entitled to expect that the Commissioner must move to finalise taxes within a limited period of time, especially if there has been delay in the Commissioner getting information indicating shortfall of tax due to fraud or evasion by the taxpayer?