A local sale of goods or a supply of services by a GST-registered business will usually be:

- for a GST-inclusive price/fee; and

- accompanied by a tax invoice confirming the GST-inclusive price and the 10% (1/11th) GST included in the price/fee.

When to look out for GST on land sales

The price and GST on a sale of real estate in Australia can be far less clear. Although a majority of sales of residential property are not subject to GST, sales broadly of:

- new residential premises (where not tenanted for at least five years);

- vacant land that can be used for residential development; and

- commercial residential premises;

are generally (GST) taxable supplies at settlement where the sale is by a seller who is either registered or required to be registered (perhaps solely required to register due to the sale). There are some exceptions.

Unanticipated GST and reducing GST with the margin scheme

Sometimes the parties can be caught unaware of a GST liability on the land sale or of an opportunity to apply the margin scheme to a sale of residential land under Division 75 of the A New Tax System (Goods And Services Tax) Act 1999 so a GST rate lower than 10% can be applied. A margin scheme rate lower than the 10% rate (or 1/11th of the GST inclusive price) will suit:

- a purchaser:

- not entitled to claim a GST credit (purchaser credits are not available when the margin scheme is applied to the purchase) ; and

- liable for stamp duty calculated ad valorem based on the (lower) purchase price plus GST; and

- the vendor who receives a higher nett price.

GST-inclusive or GST-exclusive price in the contract?

Normally a price for land is GST-inclusive under a contract in NSW.

Still, a purchaser should be vigilant when purchasing real estate where GST could apply. The current 2019 Law Society NSW and Real Estate Institute NSW contract of sale of land (the NSW contract) now has a number of checkboxes and GST residential withholding details which should indicate if GST is to apply when a proposed contract is received from the vendor. However where vendor agents and conveyancers are unaware or unsure about whether GST applies these can be left unchecked or incomplete when they should be proposed checked and completed.

The general conditions in the NSW Contract state that:

Normally, if a party must pay the price or any other amount to the other party under this contract, GST is not to be added to the price or amount. (Emphasis added)

General condition 13.2

That normal case thus matches a GST-inclusive price one is used to seeing on a tax invoice for goods or services from a supplier. However beware a contract which reveals that the purchaser must pay the price “plus GST” (so the price is GST-exclusive and general condition 13.2 is thus overridden) in a special condition even where less than obviously so: see Booth v Cityrose Trading Pty Ltd [2011] VCAT 278.

The importance of the terms of the contract, and the imperative to pick up an exceptional GST-exclusive special condition, is apparent from the NSW Court of Appeal decision in Igloo Homes Pty Ltd v Sammut Constructions Pty Ltd [2005] NSWCA 280. In that case a price plus GST (GST exclusive) provision in a 2000 edition NSW contract permitted the vendor to recover an additional amount of $250,000 on account of GST even though a series of misunderstandings (or worse) indicated that:

- the vendor had put the properties on the market at a price inclusive of GST;

- the purchaser had intended the price it offered to be inclusive of GST;

- the selling estate agent had intended the price agreed upon to be inclusive of GST;

- the selling estate agent was the vendor’s agent for the purpose of negotiating the sale and the price;

- the selling estate agent had given written advice to the vendor of the terms agreed;

- the vendor’s directors had intended the price to be the price agreed plus $90,909 on account of GST applying the margin scheme;

- neither party had intended the price to be the price agreed plus $250,000 on account of GST;

- the vendor had settled the sale even though GST of any amount and other amounts due at settlement hadn’t been paid by the purchaser;

- at settlement the vendor had accepted the price agreed and undertook to provide a tax invoice; and

- the purchaser’s mistake as to the effect of the contract was induced by the vendor’s agent who knew of and intended that outcome.

Contract could not be rectified

The evidence in the case showed that the purchaser did not understand GST and the margin scheme and had not examined the contract to identify the GST-exclusive special condition. It was found that the vendor’s conveyancer’s and the agent’s conduct described above was not so wrongful that the “rectification” of the contract sought on appeal was justified: a rewriting of the contract by the courts to reset the price as GST-inclusive.

Add the GST inclusive amount in the box to avoid an “Igloo”

The 2019 NSW contract includes a box on the front page:

The price includes GST of: $ _________

however the box is marked “optional”. It is in a purchaser’s interests to ensure this box is completed before contracts are exchanged so a purchaser’s liability for a “plus GST” amount above the agreed contract price can be countered for whatever reason.

The margin scheme and the price

One reason the parties may not complete this box is that the parties do or would seek to apply the margin scheme where GST must be charged. Eligibility for the margin scheme and thus a GST rate lower than 1/11th of the sale price is limited – see Eligibility to use the margin scheme at the ATO website. A GST liability under the margin scheme needs to be calculated by the vendor and the vendor may not have performed the calculation in time for the exchange of contracts. A further requirement of using the margin scheme is that the parties must agree to apply it under their contract (another checkbox on the NSW contract).

Under the consideration method for applying the margin scheme, which will usually be the only method applicable to property acquired on or after 1 July 2000, a margin scheme GST is 1/11th of the margin viz. the margin is the difference between the property’s selling price and the original purchase price. That is, the sale price less the purchase price equals the margin.

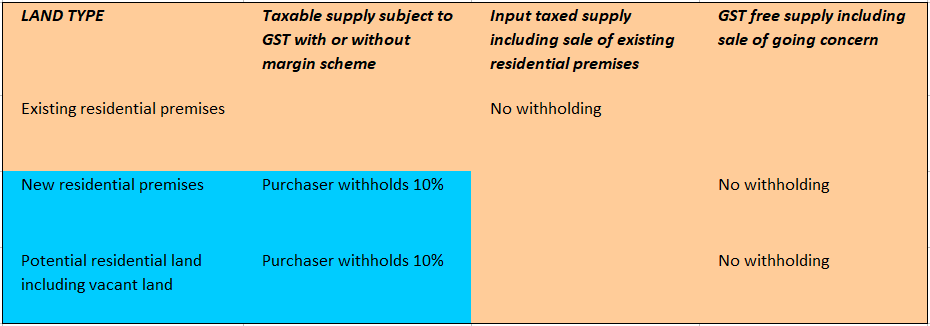

The GST residential withholding amount when the margin scheme applies

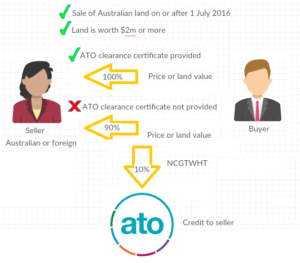

The margin scheme GST and rate differs from the flat 7% GST residential withholding amount which a purchaser must usually withhold at settlement based on the vendor’s notification that margin scheme GST applies on the contract. GST residential withholding was introduced in 2018 to require a purchaser to withhold an amount to meet the GST on the sale (taxable supply) of residential land at settlement. The GSTRW amount is paid by the purchaser to the Australian Taxation Office at settlement as an approximation of the margin scheme GST with credit given to the vendor for the payment.

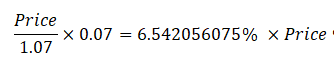

The 7% GST residential withholding amount is presently set by sub-sections 14-250(6)-(8) of Schedule 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953. Under sub-section 14-250(7) the 7% rate is applied to the “contract price” to determine the amount that must be withheld. It is to be remembered that the 7% is not the GST payable by the purchaser so a calculation treating a notionally GST-exclusive price as the price in the 7% calculation viz.

viz. 6.542056075% of the contract price on a supposed GST-inclusive basis withheld as GST residential withholding is not compliant either with this author’s understanding of sub-sections 14-250(6)-(8) or with the ATO website guidance on withholding on GST at Settlement. It should be 7% x Price.