The writer has been reading about opportunity to replace lost trust deeds with a replacement deed from professional suppliers of replacement trust deeds, in SMSF Adviser and in other places. The writer is unconvinced that these replacement deeds are going to be legally effective particularly in relation to trust deeds to which the law in New South Wales applies.

Trust deeds lost in SA – Jowill Nominees Pty Ltd v. Cooper

On 2 July 2021 SMSF Adviser suggested that the South Australian case Jowill Nominees Pty Ltd v. Cooper [2021] SASC 76 provides an insight into issues a court will consider when a trust deed has been lost. This case concerned how trust rules of a trust governed by South Australian law can be varied by the SA Supreme Court on the application of the trustee pursuant to section 59C of the Trustee Act (SA) 1936. In the writer’s view this decision says nothing about variation of trust rules beyond the confine of a SA Supreme Court section 59C application.

Section 59C differs from the Trustee Acts to similar effect in other Australian jurisdictions including section 81 of the Trustee Act (NSW) 1925.

Regularity supports that there is a SMSF where its deed is lost

Where a trust, such as a self managed superannuation fund (SMSF), has been running for some time the trustee may be able to rely on the presumption of regularity to support the operation of the trust where the trust deed is lost.

The presumption of regularity is an evidentiary rule. It can apply where there is a gap in evidence about a prior act but where later acts and circumstances indicate likelihood that the prior act was performed. So in:

- Sutherland v. Woods [2011] NSWSC 13 the NSW Supreme Court accepted that a SMSF trust deed and resolutions of a trustee of an active SMSF were signed on balance of probability although signed versions of these documents were missing from the evidence in the case; and

- Re Thomson [2015] VSC 370 the Victorian Supreme Court treated a SMSF as operative in conformity with trust rules in a supposed later deed of variation even though an earlier deed of variation of the trust deed of the SMSF was lost and only an unexecuted version of the later deed of variation of the trust deed was available in evidence. Probabilities, and the surrounding facts such as the ongoing acceptance of the accounts of the SMSF based on the supposed later deed of variation, indicated likelihood that these deeds of variation had been completed and executed.

It is clear from the cases where the presumption of regularity is sought to be relied on that a court or tribunal will presume to aid a trustee unable to produce a missing deed only after an exhaustive search by the trustee for it:

He cannot presume in his own favour that things are rightly done if inquiry that he ought to make would tell him that they were wrongly done.

Lord Simons in Morris v. Kanssen [1946] AC 459 at p. 475

Where a trustee of a trust, that has lost the trust deed of the trust, finds itself in dispute with the Commissioner of Taxation the presumption of regularity can counter the burden of proving the establishment of the trust on the trustee imposed by Part IVC of the Taxation Administration Act (C’th) 1953. See our post The burden of proof in a tax objection

The presumption of regularity is of procedural and not of substantive aid to establishing that a trust has been operating for some time in conformity with a valid and effective trust deed containing trust terms consistent with that operation where the trust deed cannot be produced. In the absence of evidence of the precise terms of a power of amendment, which is an exceptional power that can’t be presumed, the presumption of regularity, though, gives no substantial basis for amendment of trust terms to bring the terms of a SMSF trust deed back to terms that can be produced:

94. Variation of the terms of a trust (including by way of conferral of some new power on the trustee) is not something within the ordinary and natural province of a trustee. It is not something that it is “expedient” that a trustee should do; nor, fundamentally, is it something that is done “in the management or administration of” trust property. A trustee’s function is to take the trusts as it finds them and to administer them as they stand. The trustee is not concerned to question the terms of the trust or seek to improve them. I venture to say that, even where the trust instrument itself gives the trustee a power of variation, exercise of that power is not something that occurs “in the management or administration of” trust property. It occurs in order that the scheme of fiduciary administration of the property may somehow be reshaped.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at para 94

It follows that the presumption of regularity gives the trustee latitude to administer a trust on a presumed generic basis consistent with how that trust has been administered since inception where the trustee cannot produce the trust deed containing the trust terms. That presumption, though, would not ground alteration of trust terms where terms of a power of amendment which may not exist at all, cannot be specifically drawn on from the original trust instrument and complied with.

Law on amending lost trust deeds

How terms of a trust governed by the laws of New South Wales can be varied was considered by the Court of Appeal in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367. Re Dion Investments concerned an application to the Supreme Court to vary a trust deed of a trust by modernising its provisions for the benefit of the beneficiaries of the trust. In the writer’s view it is this Court of Appeal decision (by Barrett JA, whose decision Beazley P and Gleeson JA agreed with), not Jowill Nominees Pty Ltd v. Cooper, that gives insights into issues courts and tribunals, especially those in NSW, will consider when the effectiveness of instruments to amend trust terms:

- where the trust deed of the trust has been lost and the power of amendment is not precisely known; or

- in other circumstances where the variation to trust terms sought is not supported by, or are beyond, the power of amendment contained in the trust instrument such as in Re Dion Investments;

is to be considered.

Alteration of a trust by its founders

In the absence of a reserved power of amendment in a trust deed, can the trustee and the founders of a trust take action by a subsequent deed to vary an original trust deed (OTD)? The NSW Court of Appeal in Re Dion Investments indicates not. Barrett JA dispels this possibility where trusts and powers of the trust have been “defined” in an OTD:

41. Where an express trust is established in that way by a deed made between a settlor and the initial trustee to which the settled property is transferred, rights of the beneficiaries arise immediately the deed takes effect. The beneficiaries are not parties to the deed and, to the extent that it embodies covenants given by its parties to one another, the beneficiaries are strangers to those covenants and cannot sue at law for breach of them. The beneficiaries’ rights are equitable rights arising from the circumstance that the trustee has accepted the office of trustee and, therefore, the duties and obligations with respect to the trust property (and otherwise) that that office carries with it.

42. Any subsequent action of the settlor and the original trustee to vary the provisions of the deed made by them will not be effective to affect either the rights and interests of the beneficiaries or the duties, obligations and powers of the trustee. Those two parties have no ability to deprive the beneficiaries of those rights and interests or to vary either the terms of the trust that the trustee is bound to execute and uphold or the powers that are available to the trustee in order to do so. The terms of the trust have, in the eyes of equity, an existence that is independent of the provisions of the deed that define them.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at paras 41 to 42

Barrett JA then illustrates the point by this example:

43. Let it be assumed that on Monday the settlor and the trustee execute and deliver the trust deed (at which point the settled sum changes hands) and that on Tuesday they execute a deed revoking the original deed and stating that their rights and obligations are as if it had never existed. Unless some power of revocation of the trusts has been reserved, the subsequent action does not change the fact that the trustee holds the settled sum for the benefit of beneficiaries named in the original deed and upon the trusts stated in that deed. The covenants of a deed may be discharged or varied by another deed between the same parties (West v Blakeway (1841) 2 Man & G 751; 133 ER 940) but the equitable rights and interests of a beneficiary cannot be taken away or varied by anyone unless the terms of the trust itself (or statute) so allow.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at para 43

Alteration of a trust by all beneficiaries of a trust

SMSF Adviser and some SMSF deed suppliers express the view that persons who can compel the due administration of the trust can complete a replacement deed that varies and replaces a lost SMSF trust deed.

This view relies on a rule of equity from Saunders v. Vautier (1841) [1841] EWHC J82, 4 Beav 115, 49 ER 282. The rule is that where all of the beneficiaries of a trust are sui juris (of adult age and under no legal disability), the beneficiaries may require the trustee to transfer the trust property to them and terminate the trust. In Re Dion Investments, Barrett JA. recognises that this rule can entitle beneficiaries relying on the rule to require that the trustee hold the trust property on varied trusts:

but, if they do so require, the situation may in truth be one of resettlement upon new trusts rather than variation of the pre-existing trusts (and the trustee may not be compellable to accept and perform those new trusts: see CPT Custodian Pty Ltd v Commissioner of State Revenue [2005] HCA 53; 224 CLR 98 at [44]).

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at para 46

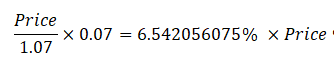

For a trust that is a SMSF impediments to and implications of variation by the force of using the rule from Saunders v. Vautier are:

- relatives and other dependants beyond the members of a SMSF, being all of the beneficiaries, must consent to using the rule from Saunders v. Vautier. Children, and others lacking legal capacity, who cannot consent to using the rule, are beneficiaries who can complicate use of the rule to vary a SMSF trust: Kafataris v. Deputy Commissioner of Taxation [2008] FCA 1454; and

- if the beneficiaries do apply the rule from Saunders v. Vautier, resettlement of a SMSF trust on taking that action gives rise to:

- CGT event E1 or E2 for each of the CGT assets of the SMSF under Part 3-1 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997. It follows that action taken by SMSF beneficiaries in reliance on the rule from Saunders v. Vautier will have comparable capital gains tax consequences to a transfer of all members’ benefits to a newly established SMSF; and

- prospect that a new ABN and election to become a regulated superannuation fund for a new resettled SMSF will by required by the regulator.

Much reliance is placed by SMSF Adviser and by deed suppliers’ websites promoting replacement deed services on Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd. [2004] NSWSC 161. In Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd. . Hamilton J of the NSW Supreme Court, as a matter of expediency, allowed beneficiaries to vary a SMSF trust deed beyond limitations in the amendment power in the trust deed utilising the rule in Saunders v. Vautier on this basis:

20. Since it is appropriate that the trustee act upon the informed consent of beneficiaries who are sui juris and unnecessary applications to the Court for empowerment are not to be encouraged, I propose to adopt the course followed by Baragwanath J in the New Zealand case. I do not propose to make an order under s 81 of the TA empowering the making of the amendment, although I have expressed the view that the Court has power to do so and would be prepared to do so if it were necessary. Rather, I shall make an appropriate declaratory order to the effect that it is expedient that the proposed deed of amendment be entered into and that it will be appropriate for the trustee to act in accordance with it.

Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd. [2004] NSWSC 161 at para. 20

Update of trust terms by a court

The Court of Appeal in Re Dion Investments agreed with Young AJ, the primary judge, that post-1997 court decisions, including Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd., which relied on a misunderstanding of the extent of court power to vary trust deeds, particularly in relation to the statutory powers of a court to alter the terms of the trust viz. the aforementioned section 81 in NSW and section 59C in SA, which misunderstanding originated from this obiter dicta of Baragwanath J in Re Philips New Zealand Ltd [1997] 1 NZLR 93

The Court will not willingly construe a deed so as to stultify the ability of trustees, having proper consents, to amend a deed to bring it into line with changing conditions.

Re Philips New Zealand Ltd [1997] 1 NZLR 93 at page 99

were not correctly decided. Barrett JA said:

100. For these reasons, I share the opinion of the primary judge that the post-1997 decisions that have proceeded on the basis that variation of the terms of a trust is, of itself, a “transaction” within the contemplation of s 81(1) rest on an unsound foundation. The court is not empowered by the section to grant power to the trustee to amend the trust instrument or the terms of the trust. It may only grant specific powers related to the management and administration of the trust property, being powers that co-exist with (and, to the extent of any inconsistency, override) those conferred by the trust instrument or by law.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at para 100

In particular. the decision in Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd. and the other post-1997 decisions referred to in Re Dion Investments cannot be reconciled with the Court of Appeal decision in Re Dion Investments where Barrett JA found:

96. In such cases, however, the creation of what is, in terms, a power of the trustee to amend the trust instrument is a superfluous and meaningless step. When the court, acting under s 81(1), confers on a trustee power to undertake a particular dealing (or dealings of a particular kind), “it must be taken to have done it as though the power which is being put into operation had been inserted in the trust instrument as an overriding power”: Re Mair [1935] Ch 562 at 565 per Farwell J. The substantive power that the court gives comes into existence by virtue of the court’s order. It does not have its source in the terms of the trust. There is no addition to the content of the trust instrument. That content is supplemented and overridden “as though” some addition had been made to it. The terms of the trust are reshaped accordingly.

97. Conferral of specific new powers pursuant to s 81(1) should not be by way of purported grant of authority to amend the trust instrument so that it provides for the new powers. Rather, the court’s order should directly confer (and be the sole and direct source of) the powers which then supplement and, as necessary, override the content of the trust instrument. And, of course, the only specific powers that can be conferred in that direct way are those that fall within the s 81(1) description concerned with management and administration of trust property.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at paras 96-97

A variation relying on a power of amendment in trust terms is not a variation of a trust deed but a variation of trust terms contained in a trust deed. Barrett JA explained this in Re Dion Investments:

44. It is, of course, commonplace to speak of the variation of a trust instrument as such when referring to what is, in truth, variation of the terms upon which trust property is held under the trusts created or evidenced by the instrument. A provision of a trust instrument that lays down procedures by which it may be varied is, of its nature, concerned with variation of the terms of the trust, not variation of the content of the instrument, although the fact that it is the instrument that sets out the terms of the trust does, in an imprecise way, make it sensible to speak of amendment of the instrument when the reference is in truth to amendment of the terms of the trust.

45. Where the trust instrument contains a provision allowing variation by a particular process, the situation is one in which the settlor, in declaring the trust and defining its terms, has specified that those terms are not immutable and that the original terms will be superseded by varied terms if the specified process of variation (entailing, in concept, a power of appointment or a power of revocation or both) is undertaken. The varied terms are in that way traceable to the settlor’s intention as communicated to the original trustee.

Barrett JA in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. [2014] NSWCA 367 at paras 44-45

Significance of the power of amendment as expressed in an OTD

A power of amendment of a SMSF, or any other express trust, is a precise reflection of the settlor’s (founder’s) intention of conditions for amendment of the trust communicated in the trust terms in the OTD and supplies the only lawful way trust rules in a trust deed, otherwise immutable, can be amended aside from narrow exceptions:

- where beneficiaries can invoke the rule in Saunders v. Vautier and, by doing so, resettle the SMSF on a new trust; or

- by court order to vary trust terms or, in NSW, to allow dealings of a particular kind despite trust terms, in accordance with a state or territory Trustee Acts such as section 59C of the Trustee Act (SA) 1936 and section 81 of the Trustee Act (NSW) 1925;

as considered above.

Amendment practice

It follows that a power of amendment in an OTD of a trust:

- needs to remain, as it was in the OTD, as a term of the trust unless the power of amendment itself can be amended, should that be possible and has so been amended; and

- is best extracted, repeated and given prominence in a deed of variation which replaces the other trust terms of a trust so that trust terms are clear and traceable on an ongoing basis.

Extraction and repeat of a reserved power of amendment from an OTD is not always just a matter of extracting the paragraph or paragraphs in the OTD containing the power of amendment. In the writer’s experience powers of amendment in older SMSF OTDs are frequently premised on laws and practices that prevailed when the superannuation trust was established e.g. such as in the former Occupational Superannuation Standards Act (C’th) 1987 and practices relating to now redundant regimes of employer sponsored superannuation. To remain traceable to the settlor’s (founder’s) intention as communicated to the original trustee, conditions specified for amendment in a power of amendment based on laws and practices, even where those laws and practices have evolved or become redundant since establishment of the trust; need to be complied with and reflected cogently in the extraction and repeat of the power of amendment in a deed of variation, within reason, if the power of amendment is to remain as a trust term in an exercisable form in the deed of variation.

When can a power of amendment in an OTD itself be amended?

Amendment of the power of amendment itself may be possible but unlikely if the amendment provision in the OTD itself does not expressly permit it. In Jenkins v. Ellett [2007] QSC 154, Douglas J. stated:

The scope of powers of amendment of a trust deed is discussed in an illuminating fashion in Thomas on Powers (1st ed., 1998) at pp. 585-586, paras 14-31 to 14-32 in these terms:

“In all cases, the scope of the relevant power is determined by the construction of the words in which it is couched, in accordance with the surrounding context and also of such extrinsic evidence (if any) as may be properly admissible. A power of amendment or variation in a trust instrument ought not to be construed in a narrow or unreal way. It will have been created in order to provide flexibility, whether in relation to specific matters or more generally. Such a power ought, therefore, to be construed liberally so as to permit any amendment which is not prohibited by an express direction to the contrary or by some necessary implication, provided always that any such amendment does not derogate from the fundamental purposes for which the power was created ….It does not follow, of course, that the power of amendment itself can be amended in this way. Indeed, it is probably the case that there is an implied (albeit rebuttable) presumption, in the absence of an express direction to that effect, that a power of amendment (like any other kind of power) cannot be used to extend its own scope or amend its own terms. Moreover, a power of amendment is not likely to be held to extend to varying the trust in a way which would destroy its ‘substratum’. The underlying purpose for the furtherance of which the power was initially created or conferred will obviously be paramount.”

Jenkins v. Ellett [2007] QSC 154 Douglas J. at paragraph 15

One can see the parity between what was said in Jenkins v. Ellett and in Thomas on Powers and in paragraph 94 in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd., as set out above, about a trustee’s proper role not being concerned to question or improve trust terms. See the writer’s article Redoing the deed https://wp.me/P6T4vg-3x#rtd

Update of the power of amendment?

The writer sees confusion among SMSF deed suppliers over the difference between the OTD and the trust terms in the OTD and who consequently fall into the trap of treating the power to amend as updatable by the same power to amend.

So instead of relocating the power of amendment in the OTD to updated trust terms, suppliers simply replace that power with their own take on an apt power of amendment departing from Barrett JA’s dictum that it is not for the trustee, far less a variation deed supplier, to “question the terms of the trust or seek to improve them”. Following Re Dion Investments and Jenkins v. Ellett a replacement of a power of amendment that is not amendable is a deviation from the power of amendment prone to be:

- beyond the power of:

- the parties entrusted with the power of amendment; and

- a court, even if an order of the court for the replacement power had been sought; and

- thus void.

Later deeds of variation of SMSFs based on a deviation

As in Re Thomson trust deeds of SMSFs will likely be varied more than once so that trust terms (governing rules) can better reflect evolving law and practice with SMSFs. An unlawful replacement of a power of amendment which deviates from the power of amendment in the OTD of a SMSF lays a trap when a trustee seeks to make a further amendment to the trust terms of the SMSF: Based on the above authorities a further deed of variation reliant on the “updated” power of amendment in an earlier deed of variation, rather than the power of variation in the even earlier OTD of the SMSF, will fail and be void unless the updated power of amendment in the earlier deed of variation is in conformity with the power of amendment in the OTD.

So are replacement SMSF trust deeds a scam?

The writer suspects many SMSF deed suppliers who supply replacement SMSF deeds don’t understand or follow the implications of Re Dion Investments. As a considered NSW Court of Appeal decision Re Dion Investments is binding legal precedent that rejects the authority of first instance NSW Supreme Court decisions referred to and discussed by the Court of Appeal, including Re Bowmil Nominees Pty. Ltd., that rest on an “unsound foundation” .

It is unfortunate that these cases are still being used as spurious authority on the websites of SMSF deed suppliers in support of claims that lost SMSF deed replacement deeds are of greater efficacy as variations of a trust deed than courts and tribunals, especially NSW courts, will be prepared to accept or order following Re Dion Investments. The writer wouldn’t say these claims are a scam necessarily because, as this post shows, the present state of law is complicated, difficult and more restrictive than understood by courts in the post-1997 cases referred to in Re Dion Investments.

The current law appears to be that if a trustee wants to vary a SMSF trust deed, which is “not something within the ordinary and natural province of a trustee” especially in NSW, the parties given power to amend under a power of amendment must locate, have and rely on that power in or derived from the OTD to successfully amend terms of a SMSF trust without resettling it.

Other solutions, aside from supreme court applications allowed under:

- section 81 of the Trustee Act (NSW) 1925, as pursued in Re Dion Investments

- section 59C of the Trustee Act (SA) 1936, as pursued in Jowill Nominees Pty Ltd v. Cooper; or

- comparable legislation in other Australian states and territories;

which are expensive litigation, are unlikely to be legally effective.

It follows that every effort should be made to find trust terms in an OTD so that the power of amendment in the deed will be carefully complied with when an amendment of a trust deed is to be undertaken. That includes where there have been earlier deeds of variation of the trust terms of a SMSF whose validity also rests on, and must be derived from the reserved amendment power defined in the OTD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author acknowledges the articles:

- A matter of trusts – Presumption of regularity to the rescue? Milton Louca and Phil Broderick, Taxation in Australia March 2018 at page 436

- The powers of a Court to vary the terms of a trust A consideration of in Re Dion Investments Pty. Ltd. (2014) 87 NSWLR 753 A paper presented to the Society of Trust and Estates Practitioners – NSW Branch Wednesday 21 October 2015 by Denis Barlin of counsel (who appeared as counsel for the section 81 applicant in the case)

that were useful in preparing this post and which contain greater detail on the issues discussed. The author also expresses his gratitude that these articles have been made available openly online.