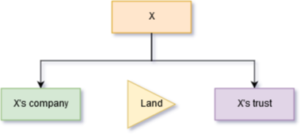

Suppliers of offshore companies often supply companies to international clients with the promise that the company will give rise to no or little income tax. What they might really mean is the tax that applies in the offshore place of incorporation or the offshore place of operation of the company. The promise may not be informative about income tax implications in the place of tax residence of the client of taking on the offshore company.

It is useful for Australians looking to acquire an offshore company, and for offshore company suppliers who may supply an offshore company to them, to know about how offshore companies may be treated for Australian income tax purposes. And the involvement of the offshore company supplier in the company may be significant to what that treatment may be.

When offshore companies are controlled foreign corporations

Australia has had a controlled foreign corporations (“CFCs”) regime since 1990 which applies to treat an offshore company controlled by Australian tax residents (“AUTRs”) as a CFC. Like with other CFC regimes, the CFC itself is not, by virtue of being a CFC, treated as a tax resident of Australia generally subject to Australian income tax on its worldwide income; nonetheless the regime functions by attributing offshore income of the CFC to its AUTR controllers. So, although tax may be low on the company in the country of operation of the company, the AUTR faces Australian income tax on the income of the CFC even where the income of the CFC remains unrepatriated from the CFC.

The CFC regime has an active income exemption which applies to exclude income earned by a CFC carrying on an active business in an offshore place from attribution to AUTRs. Where the active income exemption can apply to the CFC an offshore company supplier may be better placed to make good on their promise of low income tax to an Australian client.

Another way of making good on the promise, but a way which is not, in any way, legal under Australian laws, including under the associate-inclusive control tests in the CFC rules, is to hide the Australian control of the offshore company from Australian authorities and from others whom it may concern. Offshore company suppliers have been known to do this by providing local-based company directors and nominee shareholders who follow the directions of the client through opaque protocols, which can be in various forms, to give the client the necessary control and assurance that the client’s directions concerning the offshore company will be followed.

Offshore company is an Australian tax resident after all?

A offshore company under covert directions of AUTRs not only faces the risk that its income will be attributed as attributable income taxable in Australia under the CFC regime but also faces possible treatment as an Australian tax resident, itself. In that eventuality Australian tax authorities won’t need to rely on the CFC regime to tax the income of the offshore company in Australia.

When a company will be treated as an Australian tax resident

Under the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 a company is resident in Australia if:

it is incorporated in Australia or, if not incorporated in Australia, if it carries on business in Australia and has either its central management and control in Australia or its voting power controlled by shareholders who are residents of Australia

(definition of “resident” or “resident of Australia” in sub-section 6(1))

This is similar to the formulation of tax residence of companies that applies in most OECD countries.

The highest court in Australia, including on tax matters, is the High Court of Australia. In the 1973 case of Esquire Nominees Ltd. v. Federal Commissioner of Taxation, Gibbs J., who lead the High Court in this case, observed that:

- “the real business [of a company] is carried on where the central management and control actually abides”; and

- “the question where a company is resident is one of fact and degree”.

In Esquire Nominees, the High Court was able to find that a Norfolk Island company was not centrally managed and controlled from Australia despite evidence that Australian-based accountants:

- formulated a tax avoidance scheme involving the company acting as the trustee of a number of trusts; and

- communicated every aspect of the scheme of the trusts to the directors of the corporate trustee in Norfolk Island including how the scheme was to be carried out.

Gibbs J. was satisfied that the directors of the corporate trustee in Norfolk Island had sufficient independent power in their role, beyond the control of the Australian-based accountants, to support a finding that the central management and control of the company was on Norfolk Island. This was despite what appeared to be the whole reliance of the directors on the communications from the Australian-based accountants. The board of directors of the company did not to have to comply with directions from the Australian-based accountants. Gibbs J. found that the (board of) directors were making the decisions of the company, albeit in line with the strong influence of the Australian-based accountants, and that they met to do so on Norfolk Island.

Bywater Investments Limited v Commissioner of Taxation, Hua Wang Bank Berhad v Commissioner of Taxation

A November 2016 decision of the High Court has shown that:

- relevant matters to be taken into account in ascertaining the central management and control of a company include, but are not limited to:

- the location of the company’s registered office;

- the residency of the company’s directors;

- the residency of the company’s shareholders;

- where the company’s meetings, including its directors’ meetings, are held; and

- where the books of the company are kept;

- the place where the board of directors meets, in particular, is not sufficient, by itself, to show where the central management and control of a company, and thus the Australian tax resident status of a company is; and

- despite the outcome in Esquire Nominees, Australian courts will not always accept, just because a company has a properly appointed and functioning offshore-based board of directors, that the independence or autonomy of those directors can be inferred.

In Bywater Investments Limited v Commissioner of Taxation Hua Wang Bank Berhad v. Commissioner of Taxation [2016] HCA 45 a Sydney accountant (“G”) had complete legal and actual control of Swiss-based and Samoan-based companies despite the considerable lengths taken by G:

- to conceal the fact of G’s control of the companies; and

- to project apparent control of these companies by boards of directors in Switzerland and Samoa arranged by Swiss-based and Samoan-based offshore company and corporate services providers.

Companies involved were incorporated in the Cayman Islands and in the Bahamas. Only through the course of the Australian investigation and litigation did it become clear that various legal means, including:

- in the case of Hua Wang Bank Berhad, the device of an unredeemed secured bearer debenture which operated to suspend the rights of the offshore shareholders of the company to vote or demand a poll; and

- in the case of “JA Investments”, another significant company in the structure, appointment of G as “Appointor” with the power to appoint additional members of this company who in turn could remove directors;

had been devised to give G control of the companies.

The abrogation exception

The High Court in Bywater Investments Hua Wang Bank Berhad found that, although the central management and control of a company will ordinarily be where meetings of its board are conducted; a long line of authorities, including Esquire Nominees and the UK House of Lords decision in Unit Construction Co Ltd v Bullock [1960] AC 351, identify a significant exception where a board of directors abrogates its decision-making power in favour of an outsider, and the board operates as a puppet or cypher, effectively doing no more than noting and implementing decisions made by the outsider as if they were, in truth, decisions of the board.

In Bywater Investments Hua Wang Bank Berhad it was found that G was such an outsider in control of companies that made the decisions of each company. These decisions were implemented as decisions of the boards of the Samoan-based and Swiss-based companies and the central management and control of these companies, was with G, the outsider, who was thus carrying on the business of each company in Australia.

Place of effective management of offshore companies

In the case of the Swiss-based companies, where a consideration of the place of effective management was also relevant under the applicable double tax treaty between Switzerland and Australia , the finding viz. that that place of effective management was Australia, was no different. The consequence was that the Swiss-based companies were not entitled to protection from Australian taxation under the double tax treaty.

Demonstrating board autonomy of an offshore company

The company in Esquire Nominees was able to show that it was in the ordinary case, albeit by an indistinct or possibly by a fine margin, in contrast to the boards of directors of the companies in Bywater Investments Hua Wang Bank Berhad which failed to show that they were not puppets or cyphers of its AUTR controller.

The evidence in Bywater Investments Limited Hua Wang Bank Berhad was in stark contrast to the evidence in Esquire Nominees from which the court accepted the contention that the board of the Norfolk Island company had maintained a sufficient autonomy over decision-making by the company. In Bywater Investments Hua Wang Bank Berhad the evidence of the companies unravelled as it was found that:

- the documents and evidence produced by directors of the companies where untruthful and falsely contrived to corroborate testimony that the offshore directors operated autonomously;

- the offshore directors were a “fake”;

- the offshore ownership structure of the companies was a “ruse”; and

- the means used by G to conceal that he was the true owner of one of the companies suggested dishonesty. Every decision of consequence for that company was made by G.

It follows that AUTR clients of offshore company suppliers may be challenged to sustain that an offshore company has central management and control in an offshore jurisdiction where the offshore directors are nominees, arranged by offshore company service providers potentially identifiable as “puppets and cyphers” and not directors with real understanding of the affairs of the offshore company who are genuinely involved in the decision-making of the offshore company.

Conclusion

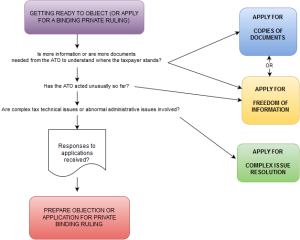

Following Bywater Investments Hua Wang Bank Berhad Australian clients of offshore company suppliers may have reason for concern that an offshore company they procure from an offshore company provider may be an Australian tax resident. Those concerns arise in the absence of real business activity by the company in the offshore place or real autonomy, in relation to the affairs of the company, given to the offshore directors in the offshore place which is evident from a holistic evaluation of the constituent legal documents of the company on which control of the company comes to rely.

Although the appearance of offshore decision-making by the company may initially show that the central management and control of the company is outside of Australia, that conclusion may not withstand a persistent scrutiny should the company be investigated, or more, and forced to produce its constituent legal documents to defend its offshore tax resident status. The outcome may be that the company is dealt with as an Australian tax resident without reliance on the CFC provisions to attribute and tax income of the offshore company to its AUTR controllers.